Free School Meals: a National Necessity

Alex Dalton and Tom Albone are part of our Data Scientist Internship Programme, their work focusses on the power of Data for Public Good. The shared focus of their intern projects is inequalities in the local Bradford area, and one of the pressing local issues affecting this local community (as well as families nationally) is free school meals.

Here they have collaborated to discuss this issue, and the data available, in more detail. This article details the uptake of free school meals across the nation, looking to this Christmas period. A second article will follow which covers the issue in the local area of Bradford.

Why are free school meals needed in the UK?

Access to affordable and nutritious food is a growing problem in the UK. Since 2008 the use of foodbanks has been increasing [1], and the impact of government austerity measures have become apparent with levels of child poverty and food insecurity escalating.

As the economic ramifications of the Coronavirus pandemic emerge from the depths of the initial health scare, businesses are closing across the UK and there has been a record spike in redundancies. Individuals and families alike are suffering emotionally and financially.

Financial status is a key indicator of food insecurity. Studies have shown how devastating household food insecurity is for health, social well-being, and child development1. Free school meals provide children with vital access to food. Vital in the immediate sense (hunger) and with longer-term consequences (poor health outcomes).

This article explores the uptake of free school meals in the UK, particularly within areas suffering from high levels of deprivation.

The UK has been reported as one of the worst-performing nations in the EU for food insecurity, with 19% of children under 15 living with food insecurity [2].

This is highlighted by the increase in uptake of free school meals: the government incentive to tackle the effects of food insecurity in children and young people. In recent months, the necessity of free school meals has been heavily discussed in the public eye and in government policy.

The UK government’s decision not to extend the free school meal scheme across school holiday periods since lockdown started has proved contentious. The drastic widening and deepening of food insecurities [2] [3] as a result of the Coronavirus pandemic and associated lockdowns resulted in the issue receiving a lot of public attention. Marcus Rashford, a professional football player, rallied support from the public and incentivised businesses’ donations. The surge of support and speed of response succeeded in raising £20million to feed children in the UK and demonstrated how crucial the free school meal scheme is for children to access food in the UK.

Eligibility for Free School Meals in the UK

The percentage of students known to be eligible for free school meals has been rising year-on-year. Since 2018, the percentage across all schools has increased from 13.6% to reach 17.3% of students eligible in 2020.

To further understand the proportion of students relying on free school meals across all the UK, it is useful to look at the distribution of eligible students for the scheme per school.

The following analysis uses data recorded by the Office for National Statistics for the 2019/20 Academic Year. The data is recorded across all schools in the UK, however for our investigation independent schools have been excluded from the dataset as they do not appear to record free school meal data.

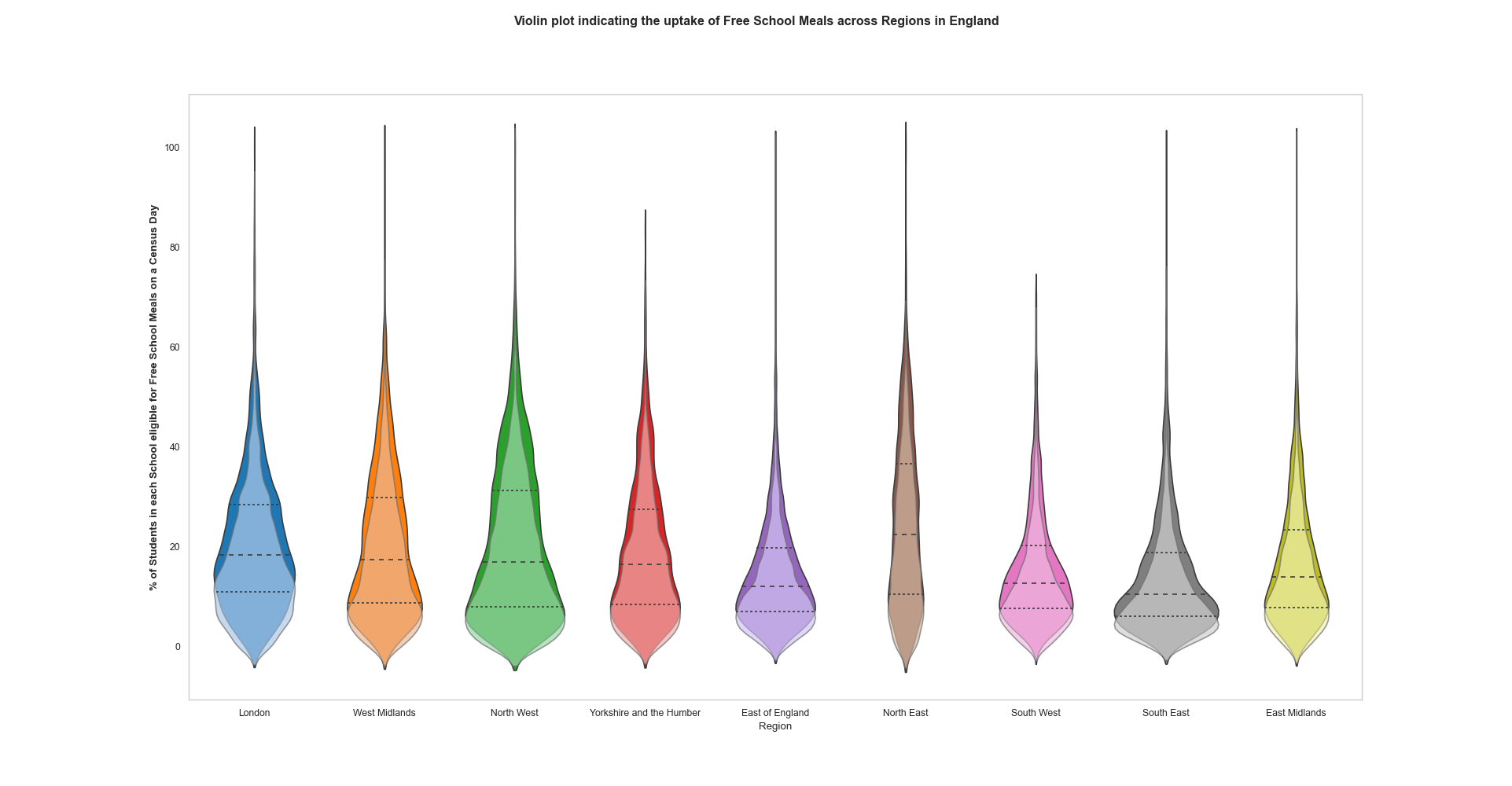

Figure 1. Plot showing the percentage of students eligible for free school meals per school on a census day in the 2019/20 Academic Year. Plots are per Region, indicating the quartiles with bw=0.1 and a uniform scale across the plots. Percentages are calculated per school using data collected by the ONS across all schools in the UK (excluding independent schools). The plot of students eligible on a census day is overlayed with the plot of students recorded actually taking free school meals on the census day (translucent violin plots). The darker edges showing those who did not take their free school meal.

It is important to note that the data refers to children who were eligible to receive, and who claimed, free school meals (FSM) by census day. The overlay of students recorded as taking FSM refers to eligible children who took a free school meal on census day. This second measure only provides an indication of what happened on the day of the census. However, for the purposes of this blog we can use them as an indicator of the proportion of those eligible that needed to use the service.

The distributions show that a significant proportion of children rely on free school meals across the country. More interesting is the variety of the distributions between Regions, illustrated by the shapes of the plots.

Northern Regions have a larger number of students that are eligible per school. Three quarters of schools (top dashed lines on plots) in the Northern Regions (e.g. North East, Yorkshire and Humber) have up to 30% of students eligible on average, with a spike of 36.5% in the North West illustrating that free school meals are more commonplace and required in these areas. In contrast, three quarters of schools in the Southern Regions (South East, South West, East of England) never exceed 20%.

The long thin violin plots, such as that of the North East show that the percentage of students eligible in schools ranges drastically across the region, with some schools having a particularly high proportion of eligible students. In comparison, the short ‘dumpy’ violins indicate the majority of schools have a similar proportion of eligible students, which here tends towards the lower end of the scale, illustrating the stark differences across the UK and inequalities in food security.

What can we learn looking forwards?

Food banks in the Trussell Trust network had been seeing year-on-year increases in levels of need; in a recent report they stated that:

“This (COVID19) crisis has landed after years of stagnant wages and frozen, capped working age benefits – leaving those on the lowest incomes vulnerable to income shocks”.

With children having spent a great deal of time off school during lockdown at home, pressures on family budgets have increased. During this time, efforts were made to provide families with free school meals despite the schools being closed. Even though this was seen as an essential need for many, it was not provided by the government until public opinion went against them.

With the economy taking hit after hit, those in the most deprived households are more likely to suffer the worst impacts. Recent data from a YouGov survey suggests that many households have fallen into food insecurity since the advent of the Covid-19 pandemic. More than three million people (6%) in the UK went hungry in the first 3 weeks of ‘lockdown’, with households reporting that a member had been unable to eat, despite being hungry, because they did not have enough food. Permanent or temporary unemployment appears to underlie lack of resources, with claims for Universal Credit approximately doubling since mid-March 2020 [4].

The demand for free school meals to be provided over the school holidays is driven by the extraordinary circumstances we all now find ourselves in.

These data let us see how issues of food security and free school meals disproportionately impact some areas more than others. As with the rate of COVID-19 infections and the government restrictions, it is useful to look at this on a local level. The city of Bradford is one such example and will be the focus of a further article.

[1] https://www.trusselltrust.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2017/07/OU_Report_final_01_08_online2.pdf

[2] Barker, M., & Russell, J. (2020). Feeding the food insecure in Britain: learning from the 2020 COVID-19 crisis. Food Security, 12(4), 865-870.

[3] Power, M., Doherty, B., Pybus, K., & Pickett, K. (2020). How COVID-19 has exposed inequalities in the UK food system: The case of UK food and poverty. Emerald Open Research, 2.

[4] https://www.nihr.ac.uk/documents/2048-food-insecurity-health-impacts-and-mitigation/24905